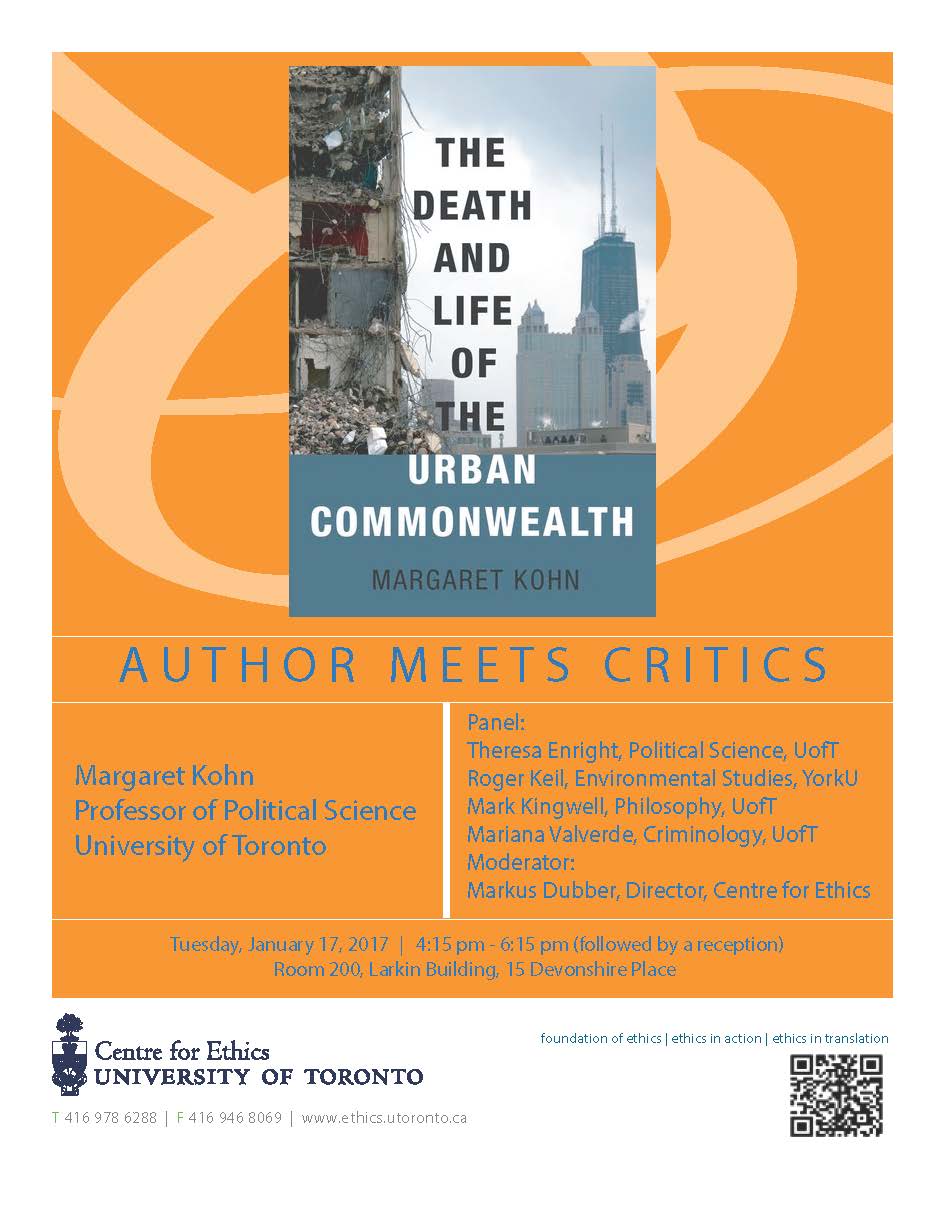

Peggy Kohn has won two awards for her recent book, The Death and Life of the Urban Commonwealth (Oxford 2016), the American Political Science Association’s David Easton Award of the Section on Foundations of Political Thought “for a book that broadens the horizons of contemporary political science by engaging issues of philosophical significance in political life through any of a variety of approaches in the social sciences and humanities” and the Dennis Judd Best Book Award of the APSA’s Section on Urban and Local Politics for “the best book on urban politics.”

has won two awards for her recent book, The Death and Life of the Urban Commonwealth (Oxford 2016), the American Political Science Association’s David Easton Award of the Section on Foundations of Political Thought “for a book that broadens the horizons of contemporary political science by engaging issues of philosophical significance in political life through any of a variety of approaches in the social sciences and humanities” and the Dennis Judd Best Book Award of the APSA’s Section on Urban and Local Politics for “the best book on urban politics.”

Here’s the citation for the David Easton Award:

Margaret Kohn’s important new book focuses our gaze on the city as the location of key struggles over the meaning of democracy and social justice in the 21st century. The theoretical core of her rich and multilayered argument is the idea of the city as a common-wealth – a collectively and historically produced social good whose benefits should be enjoyed on a basis of equality by all who live in it and contribute to its vibrancy. Drawing on the widely overlooked tradition of solidarism that was developed by French republicans in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Kohn reconstructs a theoretical justification of “the right to the city.” She presents the idea of “urban commonwealth” as an alternative to both the neoliberal model of privatizing and commodifying civic space, on the one hand, and the model of welfare state capitalism, in which the city is an afterthought, on the other. In contrast to these familiar frames, solidarism recognizes the “unearned increment” of value that accrues to property holders as a consequence of contemporary public investments and it both considers and values the contributions of past generations in producing the social good of city life. Kohn’s compelling account of solidarism offers us a new lens through which to see the injustices of dispossession, displacement, and marginalization that proceed through gentrification, the commodification of housing, the privatization of public space, and the emergence of “transit deserts.”

At almost every turn of the page, and certainly in each and every chapter, the reader of Kohn’s book encounters innovative conceptual clarifications that powerfully illuminate the normative dimensions of urban life and, more generally, invite a new way of imagining the complex relations of interdependence and interconnection that are characteristic of our age. Kohn moves seamlessly between re-readings of classic texts in the history of modern Western thought (from Locke to Marx to Hayek); she draws on rich empirical examples (from a diverse array of cities in India, Europe, and North America), and she develops thought-provoking engagements with a wide range of contemporary political theory. Her approach is admirable, as well, for its subtlety and indirectness. Rather than foreground or “sell” her (genuinely important) conceptual innovations to her readers, Kohn proceeds more humbly, putting her concepts to work to analyze concrete, social, cultural and geographic issues and events. She makes visible the political stakes of the city and traces the fault lines of past and future conflicts. The “urban commonwealth” is therefore not merely an example by which Kohn illustrates her normative political theory, but rather the site of her theorizing, and of her and our politics.