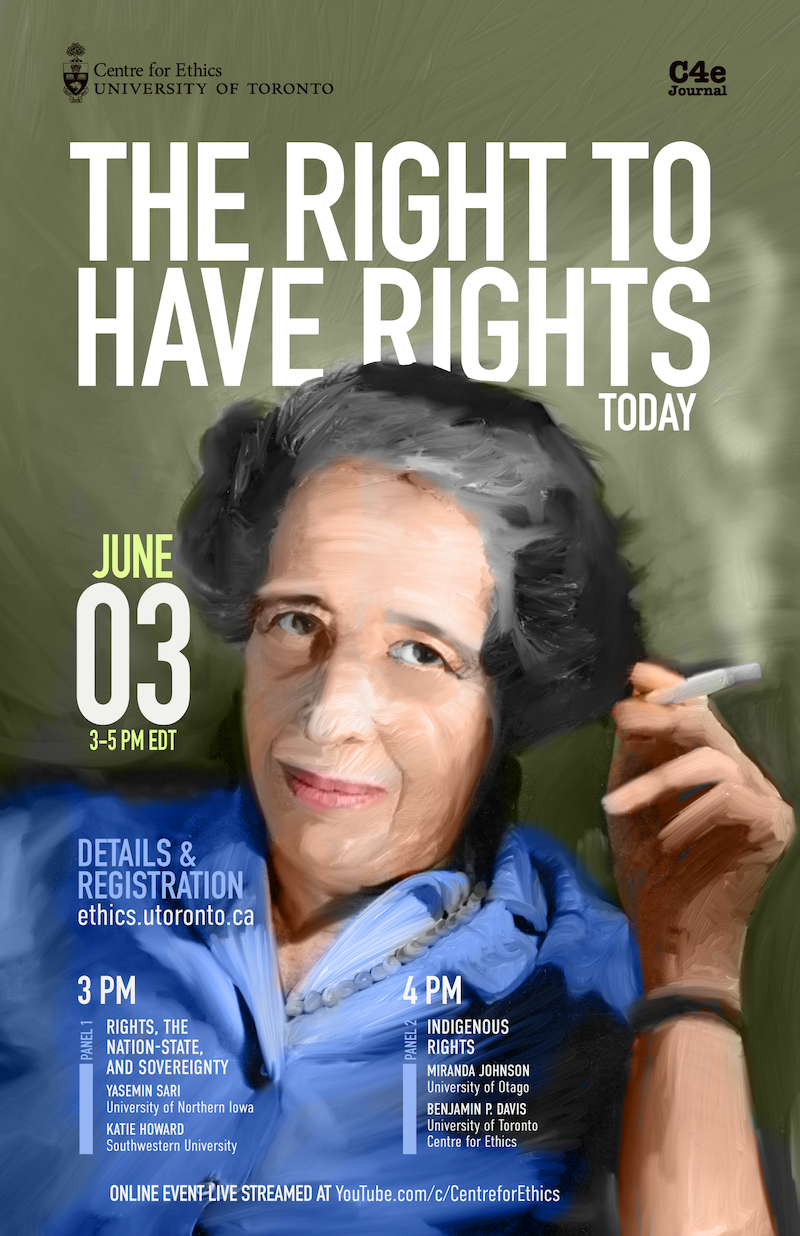

The Right to Have Rights Today

Hannah Arendt’s useful phrase ‘the right to have rights’ asks us to consider foundational rights—to consider on what ‘right’ other ‘rights’ are based. In The Rights of Others, Seyla Benhabib argues that the first right in Arendt’s phrase is addressed to humanity as a call to recognize political membership, where such a ‘right’ to membership entails legal entitlements (the plural ‘rights’). Working with a different literature, and calling into question the still-predominant North American priority of political rights over economic rights, in Basic Rights Henry Shue argues that security and subsistence rights are foundational for other rights. In still different fields and sites, theorists in Native Studies and centuries of Indigenous activism have called for land (back) as foundational to other meaningful economic or political rights, and others in Native Studies and Black Studies have asked theorists, advocates, and organizers to re-think both a strategic reliance on rights claims and a too-easy sense that the nation-state protects rights (e.g. Glen Coulthard, Red Skin, White Masks; Dionne Brand, A Map to the Door of No Return; and Rinaldo Walcott, The Long Emancipation). Finally, Paul Gilroy has recently asked us to re-imagine the history of human rights such that its genealogy begins not with Jefferson and the Declaration of Independence or Eleanor Roosevelt and the Universal Declaration, but with David Walker and Frederick Douglass (cf. Postcolonial Melancholia and Darker than Blue).

In other words, claims to human rights—what they have been, are, and could be—remain unstable into our present, part of a larger contradictory history that includes the South African white supremacist Jan Smuts calling for human rights in the preamble of the United Nations Charter while W. E. B. Du Bois took up the term in his contemporaneous Color and Democracy; or, more recently, when human rights have been invoked to argue both for and against the U.S. invasion of Iraq.

What are we to make of this conceptual instability? What histories, traditions, and cosmologies help us to understand rights claims in new ways? What sites of practice (well beyond political theory) leverage rights in the most useful ways, and what can we learn from these sites, struggles, and celebrations? At the very least, such a contested history of human rights requires what Arendt called thinking, and we look forward to thinking in community in June. Workshop proceedings will appear in a special symposium issue of C4eJournal.net.

► please register here (free)

Preliminary Schedule

3pm = 12pm Pacific/8pm UK/6am Melbourne

Panel 1: Rights, the Nation-State, and Sovereignty

Yasemin Sari, University of Northern Iowa

“The Right to Have Rights: Humanity and Substantive Belonging”

When Hannah Arendt published The Origins of Totalitarianism in 1951, statelessness—and hence, rightlessness—was the predicament of a post-War Europe. Her criticism of the condition of rightlessness struck right to the heart of the matter in her eloquent criticism of the so-called universal human rights, which since their birth in the 1789 French Declaration had been subject to a plethora of revisions and adoptions, without, however, changing what lay at their core: equality. To be sure, what Arendt diagnosed in this work was not only that human rights were being violated—for that was self-evident—but that statelessness had become a sign of the violation of what she called a “right to have rights.” What this expression implies, which I will try to make explicit, aims to lay the groundwork for articulating the conditions for the political agency of the refugee anew, while at the same time addressing Articles 3, 14, and 28 of the UDHR in the light of this analysis. By taking seriously Arendt’s argument that the right to have rights can only be “guaranteed by humanity itself,” I want to show what a concrete principle of humanity would entail in contrast to a metaphysical one that has informed previous rights-based accounts of what we owe to refugees. As such, I will argue that a concrete principle of humanity rests on a performative account of recognition that allows for the appearance of the refugee as a political agent, where such agency is rests on an “artificial equality” that motivates substantive belonging to a community.

Katie Howard, Southwestern University

“The ‘Right to Have Rights,’ the ‘Right to Life,’ and the ‘Right to Maim’”

In The Origins of Totalitarianism, Hannah Arendt traces the process by which a condition of rightlessness is produced so that the “right to life” can be challenged. This account of “statelessness,” which Arendt understands expansively as the loss of a place in the world that guarantees humanity, provides both a critique of universal human rights as inadequate, as well as the basis for a recognition of what she calls “the right to have rights.” Here, I understand “the right to have rights” to refer to the exercise or enactment of a right to struggle for rights. As I will argue, the “right to have rights” is thus a theory of action—an early articulation of the plural, non-sovereign theory of political action that Arendt develops in her later work The Human Condition. In the paper, I return to statelessness as the biopolitical site where the “right to life” is challenged and the “right to have rights” becomes legible. Turning to Arendt’s early critique of Zionism, the paper develops an account of settler colonialism as producing a new statelessness, a state of suspension held in suspension–that is, a dispossession that must be sustained, never complete. This interminable dispossession requires a different model for theorizing sovereign power and points instead to the biopolitics of what Jasbir Puar has recently termed the “right to maim”: the exercise of sovereign power as an ongoing activity that simultaneously injures and sustains (Puar 2017). How does “the right to have rights” as a mode of enactment fare with respect to the “right to maim” understood as the production (in this case, the settler colonial production) of debility? This question will motivate the reflections offered in the paper’s conclusion, which explores the embodied, affective dimensions of Arendt’s “right to have rights.”

Panel 2: Indigenous Rights

4pm = 1pm/9pm/7am

Miranda Johnson, University of Otago

“Entangled Discourses: Becoming Historical Subjects, Claiming Indigenous Rights”

In my contribution to this discussion on the ‘right to have rights today’ I want to explore the relationship between indigenous rights activism and the writing of indigenous history in the second half of the twentieth century – the long era of decolonization. The two discourses are entangled with each other such that one discourse often provides the justification for the other: the writing of indigenous history is often founded in a claim that to do so is to recognize indigenous people as rights-bearing political subjects; to make a rights claim stick often relies on a historicizing of the rights-holder. I will draw on examples from around the settler world where ‘indigenous’ was redefined in the era of decolonization. Whereas in earlier European imperial discourse, ‘native’ had referred to all peoples subject to colonial rule, in the second half of the twentieth century the term ‘indigenous’ began to be used to denote those minority peoples surrounded by permanent settler states. Over this period, discourses of indigenous rights also changed from what I have called elsewhere a discourse of ‘native assimilative rights’ to one of ‘postcolonial indigenous rights’. The emergence of postcolonial indigenous rights – where ‘postcolonial’ is more complicated than denoting the achievement of new statehood but instead refers both to the continued salience of colonial-era discourses of treaty, native title and so on along with assertions of indigenous self-determination – provoked new kinds of history-writing about indigenous peoples. The fields of Native American, Aboriginal, Māori history etc. emerged in academic discourse. Indigenous peoples were represented as historical subjects and agents not simply objects in the way of frontier settlement. Thus, I argue that the right to have rights in relation to indigeneity is bound up with the writing of indigenous people as historical subjects.

Benjamin P. Davis, University of Toronto, Centre for Ethics

“The Right to Have Rights in the Americas: Arendt, Mariátegui, and Monture in Dialogue”

This paper starts from Hannah Arendt’s use of the phrase ‘the right to have rights’ in order to consider which rights ground other rights. To read the right to have rights in the context of the Americas, I start from two contemporary readers of Arendt. First, I follow Seyla Benhabib’s form of reading the first right as the base of the second right(s), but the content I posit is different. My argument is that, in the American context, the first ‘right’ should compel justice-oriented actors to demand the repatriation of federal land to Indigenous nations, whom states such as the U.S. and Brazil have cut off from the realm of public life by forcing them onto reservations. Like the Nazi ‘herding… into ghettos and concentration camps’ that Arendt poignantly documents, American nation-states have followed such forced population transfers with ongoing deprivations of Indigenous rights, including rights to religion and voting rights. But the duty bearer for the right to have rights, in the way I am reading it here, is not just the nation-state. I also want to draw on Lida Maxwell’s reading of ‘to have’ as a call to create and to sustain a world where it is easier to achieve rights. Indeed, to assume that Indigenous nations are demanding simply increased state support can overlook claims to self-determination and the fact that in many cases what is at issue remains unceded land. To flesh out the first right in ‘the right to have rights’ as a right to land, I turn to the Peruvian Marxist José Carlos Mariátegui. Mariátegui insisted that what was called, in his time, the problem of the Indigenous person (el problema del indio) was in fact the problem of an economic order. ‘We are not content with demanding Indigenous rights to education, culture, progress, love, and heaven’, he writes against the humanitarian sentiment that loomed large in his time (and remains in ours). ‘We start by categorically demanding the right to land’. Notably, his is a challenge to taking second- and third-generation rights (here to education and culture) as foundational. Instead, he prioritizes the right to land—it is the first demand, the starting point, of those who approach questions of Indigenous rights, he says, ‘from a socialist point of view’. An interlocutor might here ask whether a right to land is simply a right to property. I conclude in dialogue with Patricia Monture’s language of a right to responsibility to land to underscore that a different epistemology, an Indigenous epistemology around land, grounds the right to land in the Americas. Thus, staging a conversation among Arendt, political theory, and Native Studies, this paper presses that basic rights in the Americas—that the right to have rights in the Americas—have always been about not simply speech or subsistence, but about the land itself.

This is an online event. It will be live streamed on the Centre for Ethics YouTube Channel at 3pm, Friday, June 3. Channel subscribers will receive a notification at the start of the live stream.

Fri, Jun 3, 2022

03:00 PM - 05:00 PM

Centre for Ethics, University of Toronto